Socialist Realism: Art or Propaganda

30.01.2020

At the exhibition “The Revolution is Dead. Long live the revolution! ”Held at the Paul Klee Art Museum and Center in Berne, one of the main themes is the aesthetic revolution. Originated with the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia, it still has a significant influence on art to this day.

The swissinfo.ch portal met with Katleen Buehler, curator of the exhibition at the Bern Art Museum, and talked about history, the one-sided view of the West, propaganda and kitsch, and the political significance of art. The editor-in-chief of the portal Larisa Biler and the head of the Russian edition of swissinfo.ch Igor Petrov talked.

Larisa Biller: The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia was a shock to Russian society. The age-old rule of tsarism was overthrown. But why is this a topic for exhibition at the Swiss Museum of Art?

Kathleen Buehler: This revolution has shocked not only Russian society. It shocked the whole world. Thematic exhibitions are always a good opportunity to look at the past and our history of the arts, in particular, to reflect on our present attitude to this topic.

To what extent is this relevant to our society? What about the division into the socialist, communist part of the world and the capitalist world? This split has become especially relevant these days. In general, there were many issues pertaining to this historic event that became decisive for the creation of our exhibition.

LB: The political movements that led to Trump's presidency and Britain's exit from the European Union are the focus of attention around the world. Obviously, the idea to create an exhibition is connected with these current events?

KB: Absolutely. In an art museum it is impossible to do only those arguments which are connected with the history of art. Art is a place where fantasy finds its space, where hope, with or without censorship, seeks expression. Since the 1930s, there has been a classic belief in the West that Stalinist art, socialist realism, is not art at all, but propaganda, and therefore simply kitsch.

I found it important to take this art seriously as art and to find out where in this top-down program there might be little freedoms and where one picture might say more than a thousand words. And it was also important to understand where the moment begins when the artist, if he succeeds, can express his critical attitude to his worldview.

LB: Besides, now is the time when ideology can exploit art?

KB: That's right. If we remember the discussions about fake news and "alternative facts", now is the moment when we are trying to cast doubt on what we see. It becomes clear that what is meant is not something they show, but something else. Therefore, at our exhibition you can well trace the relation between propaganda and the art itself.

LB: Propaganda is a negative aspect, but at the same time it can be said that art was very realistic at the time?

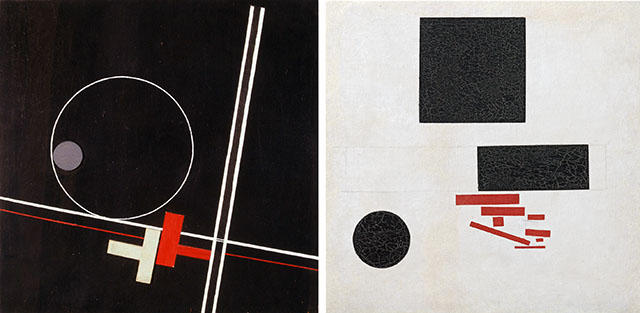

KB: This is what is most exceptional and incredible in that situation of a hundred years ago, so in some cases it can be an example. Malevich's "Black Square" was presented in 1915 at an exhibition that, by today's concepts, achieves absolute radicality in the depiction of meaninglessness.

It was an aesthetic revolution, the impact of which is still felt. And in our art, too. But after the military confusion, a government comes to power that, for the sake of communist education, promotes art that is the complete opposite of the aesthetic revolution of 1915.

In essence, this aesthetic revolution forms the basis of Western modernism. This is our art as we know it today, with all the movements that have arisen from it and have existed for over a hundred years. All this is presented at the Paul Klee Center in Berne, where there is a special respect for the aesthetic revolution. Our exhibition shows both sides of the coin, both directions in the arts that arose from both aesthetic and political revolutions.

LB: At that time there were fierce discussions about the social and political importance of art. The Russian avant-garde was "interdisciplinary" and wanted to penetrate all spheres of life.

KB: Most avant-garde artists were, from the beginning, ready to participate in the revolutionary rupture of old society, all of whom wanted to contribute to the creation of a new society, a new person, a new life.

LB: The art is very commercialized in Switzerland as well, and we know big exhibitions that are very far from reality. And if art is political, it is most often it is punished by politicians.

KB: The art market is driven by our capitalist system, and fetishes are traded on it. But at the same time, there is a non-selling art that oversees all social processes and discusses issues that are really important to society. I believe that there is no art that is not political, this applies to abstract art too.

One Hundred Years of Dadaism The Swiss avant-garde that turned the world

Even those artists who are far removed from politics are politically active even when they refuse to comment. Any statement made publicly is political. Because this is how people proclaim their values, express their opinions, share someone's point of view, or even want to influence someone.

Igor Petrov: I would like to return to the exhibition myself. How long has she been preparing and what problems have she had?

KB: We have been preparing the exhibition for exactly two years. Our colleagues at the Paul Klee Center held their exhibition in Russia and already established their first contacts. With regard to socialist realism, preparation for the exhibition proved to be very difficult for us. Because most texts, books and sources have never been translated into English or German.

In this regard, we had to rely mainly on studies conducted in Germany and in English-speaking countries, as well as on the works of American Slavists. From the outset, it was clear that this was about the view of the West, about our attitude to this art. But on this issue we could not reach an understanding with the Russian side, so it was decided mainly to show how we see this art.

IP: How did the preparatory work with your Russian colleagues go?

KB: There were little difficulties with the selection of works, because art museums in Russia do not work the same as ours. For example, in Russia it is not accepted to publish data of paintings on the Internet, otherwise it would be possible to simply look at what is available. So we had to take what was already shown in the West.

And despite that, we showcase a fantastic selection of works by Alexander Deyneka. Deinec has never been shown in Switzerland, at least to that extent and of such quality. We have wonderful works by Malevich. At the Paul Klee Center you can entrust the representation of your interests with abstract art, and we at the Bern Art Museum have a later and faster imaginative part of his work.

IP: What do you want to say in your exhibition of the world?

KB: I wanted us to look again at the relation that has been evident in the West for 100 years, namely the relation between abstraction and realism. And you also want to know people's opinions about whether socialist realism is merely propaganda or can be considered art. Because after the collapse of the Soviet Union, many artists from the former Soviet republics took to the international stage, and they rightly demand that their artistic past be taken seriously.

IP: When I first saw the poster about the exhibition, I was confused. The Russian Revolution was an immense historical and human tragedy. The brief renaissance of the Russian vanguard was followed by repression, mass executions and deportations. On the so-called "philosophical steamers" the best representatives of Russian art and intelligentsia were simply pushed abroad.

An art exhibition may exist, but the historical context should not be absent. What did you do to critically reflect the historical perspective of this art? So that people who come to the museum do not view the revolution as a leisure walk?

Revolution in Russia - 100 years of Russia and Switzerland in the era of two revolutions

KB: Your objections concern all exhibitions that will take place this year. It is absolutely clear that any simplified approach must be prevented. But we chose this motif for the poster because, even before the younger generation, the question is: are you ready for the revolution? Or is it enough for you to have a good time? We wanted to show that all revolutions at their core are a protest of the younger generation against self-sufficient people who have already found their place in society.

For me, this is the first time I have had the opportunity to study the history of the USSR. Much remains to be done in Russia. Therefore, while we come out of the phenomenon of art, but there is always a reason to talk about the historical background.

IP: Good thing you mentioned this problem. Youth issues. The question is whether the youth is ready for the revolution. At the end of March, we in Moscow could watch young people, born mostly in 2000 and not seeing anything but the current regime, suddenly hit the streets. But my question is: were there any politically colored conditions for receiving exhibits from Russia? After all, you said that any art is a policy, even neutrality is a political position.

KB: Although there were no formal restrictions, there were times when it became clear how serious we were about these works.

For example, I wanted to show the work of two artists: Alexander Vinogradov and Vladimir Dubosarsky, in a jokingly obscene, distorted form depicted a collective farm harvest festival. I saw this picture three years ago in Moscow. This is an innocent, mischievous overkill of a well-known figurative formula that we have known since the early 1940s. And I would be happy to show this huge 3x4 meter painting. It was created in the early 1990s when people enjoyed a new freedom, and yes, it is associated with some kind of kitsch, with a longing for glamor.

But here it turned out that our other Moscow colleagues, who provided us with exhibits, do not approve of this joke. As a result, we have taken other paintings by these flamboyant artists. And the scene of the celebration of the harvest can be seen only in the catalog.

IP: I was expecting to find a mention here of the bold female Pussy Wright band. In general, this is the most revolutionary, the most political art that once existed in Russia. Have you thought about it?

KB: Of course, they thought about it and included it in our movie program. We are showing a film by Milo Rau, who has collected and processed material on lawsuits in Moscow and tried to understand how the Pussy Wright group could have been sentenced. By themselves, their art as an aesthetic phenomenon in the West is not recognized as something particularly radical. But in any case, the exhibition would not be complete without mentioning o Pussy Wright.

LB: Let's go back to 1915. You mentioned Malevich's Black Square, it's an icon in the history of the arts. But you also talked about the variety of positions in this exhibition that are unique. What is your key piece of work and why?

KB: One of the key pieces for me is the trilogy "And Europe Will Be Amazed." Its author, Israeli artist Yael Bartana, shot this film in 2007-2011 at the request of the Polish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Her work consists of three parts and is an imaginary experiment as someone in Poland calls Jews back to Poland. They come and rebuild the city, and at the end of the movie, the person who called them is killed and mourned.

Bartana mentally reproduces this experiment, shows how unsuccessfully everything is, and makes it the language of the Russian Revolution films. She uses the same dynamic camera positions, this bottom-up look on young, full of hopeful individuals to visualize the hope of a revolutionary upheaval. The trilogy is incredibly impressive and compelling. And although we know that such a language of the film is associated with historical tragedies, we find ourselves electrified and at the end of the film we realize that we have hit the same fishing line again.

A work of art that can evoke such intense emotions and at the same time capture so much fear is truly brilliant. I believe that to continue to work on consciousness is an important task facing all people of the arts.

A large number of paintings from the period of socialist realism are presented at https://www.etsy.com/shop/SocrealizmComUa